The 12 Principles of Animation

Tutor: Lou Kneath

ACTION, CHARACTER & PERFORMANCE

Drew Campbell

1/10/20252 min read

The 12 Principles of Animation

The 12 principles of animation were introduced by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, two of Walt Disney’s most influential animators. They were part of Disney's "Nine Old Men," a core group of pioneering animators who defined much of what we now consider the foundation of classic animation.

Thomas and Johnston detailed these principles in their seminal book, The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation (1981), which remains a cornerstone text for animators worldwide. Their work not only shaped animation at Disney but also set a standard for the industry as a whole.

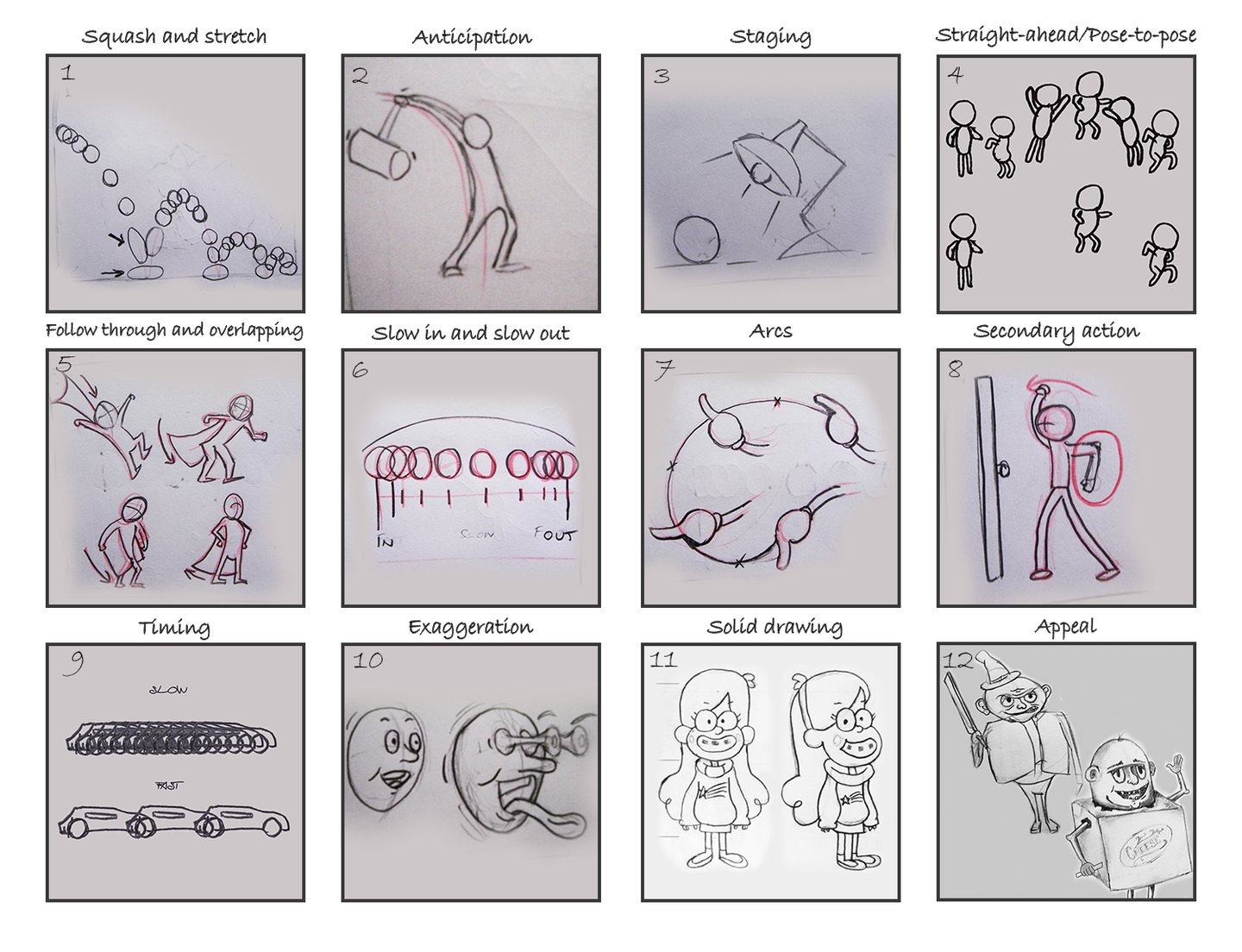

1. Squash and Stretch

This principle brings life to an object or character by showing how its shape changes under pressure or motion. It’s like the way a rubber ball flattens when it hits the ground but stretches as it bounces back. The degree of squash and stretch can signal the material’s flexibility, weight, or even emotional state.

2. Anticipation

Anticipation is about preparing the audience for what’s coming. Before a character leaps, they crouch. Before they throw, they wind up. It’s a small but critical moment that adds believability and keeps actions from feeling abrupt or disjointed.

3. Staging

This is storytelling through composition and clarity. Every shot or pose should highlight the action, emotion, or narrative intent without confusion. Imagine directing the viewer’s eye like a spotlight, guiding them to focus on what’s most important.

4. Straight-Ahead Action and Pose-to-Pose

Two ways to animate: straight-ahead is like improvising, drawing frame after frame in sequence, great for fluid, unpredictable movements. Pose-to-pose is more like choreography, starting with key moments and filling in the gaps for precision. Both are tools in your kit, and knowing when to use which is key.

5. Follow Through and Overlapping Action

When a character stops moving, not everything halts at once. Think of how a dress continues to sway or a dog's ears flop after the rest of it stops. Overlap gives weight and realism to movement—it shows that different parts move at their own pace.

6. Slow In and Slow Out

Objects and characters don’t start or stop instantly—they ease into motion and slow down before coming to rest. This principle mirrors real-world physics and adds a natural rhythm that prevents actions from feeling robotic.

7. Arcs

Most movements in nature follow curved paths, not straight lines. Whether it’s the swing of an arm or the arc of a jump, using arcs adds grace and believability. Even subtle details, like a head turn, benefit from this principle.

8. Secondary Action

This is the extra detail that enriches the primary motion. Imagine a character walking: the swing of their arms or the bounce of their hair complements the main action, enhancing the personality or mood without overwhelming it.

9. Timing

Timing is the backbone of animation. It’s not just how long an action takes, but how the spacing of frames creates weight, emotion, or intensity. A heavy object falls differently than a feather, and good timing makes those differences clear.

10. Exaggeration

Reality can sometimes be too subtle for animation. Exaggeration amplifies actions, expressions, or forms to communicate better—whether for humor, drama, or just clarity. It’s about finding the line between believable and striking.

11. Solid Drawing

This principle reminds us of the basics: characters and objects need volume, weight, and balance. They shouldn’t feel flat or flimsy. Even in stylized worlds, they need to exist with a sense of structure and believability.

12. Appeal

Every character or action should captivate the audience. Appeal doesn’t mean making everything cute or pretty; it’s about creating designs and performances that are interesting, engaging, and relatable—something people want to watch.

Business address: Voice of Drew, Carlisle, CA2 6ER | UTR: 7259771174 Copyright Drew Campbell 2024